The New Yoga Paradigm

There are virtues and drawbacks to the use of the traditional concepts and belief systems in yoga to inform its various practices. On the one hand, for many, the belief that one is engaged in an experience rooted in ancient knowledge and validated by the passage of time provides a level of confidence and reinforcement. Also, learning a new and foreign set of concepts within the context of what appears to be a holistic and coherent paradigm signals and emphasizes the ways in which learning yoga is not simply an adjustment to one’s physical exercise activities, as it might be in, say, adding a new move to one’s basketball offense or a new stitch in knitting.

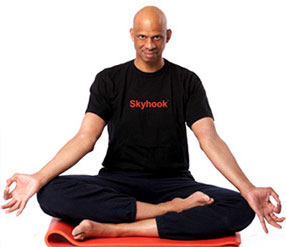

Yoga involves a transformative approach to physical activity centered more in the breath and the sense of the bodymind than in simply a new arrangement or movement of the limbs. So inviting students to learn the traditional yoga practices and belief systems can be an insightful and affirmative part of the practice and, for many, supports the dedication necessary in gaining the benefits of doing yoga.

On the other hand, the use of traditional terms and belief systems in yoga (whichever of the many belief systems of yoga one follows) can lead to a reified sense that yoga is an immutable practice and that its truths cannot be challenged or modified, even when they come into conflict with what we now know and understand about the nature of nature, including human nature, through the continued discoveries of science. Sometimes, these conflicts between traditional approaches and what we know from the science of physiology and related fields reach the point where significant modifications in both the concepts and practice of yoga are necessary. From time to time, there are fundamental changes in the basic concepts and practices – the paradigm – of any discipline that asks for evidence of truth or efficacy. This is called a paradigm shift.

Regarding yoga, some claim there can never be a paradigm shift because yoga is a divinely and unchanging gift transmitted by the gods. In this religious view, there’s an original and true yoga that is unchanging and passed down from guru to disciple over time. Rooted in belief and faith, and not troubling with little things like facts or evidence of efficacy, the religious view of yoga is widely embraced by the leaders of most yoga “lineages.”

Lineage leaders (along with countless self-anointed yoga “masters” – and what have they mastered?) generally lay claim to being the sole and rightful purveyors of what they claim to be the original and true yoga, further asserting that it is only they who can correctly guide anyone in the true practice of yoga. All other approaches are typically seen as being confused, distorted, wrong, misleading, etc.

In today’s globalized yoga scene, most styles, brands, and lineages (which are arguably stylized brands) were created in the past generation or two. For example, two of the most popular today, Vinyasa Flow and Yin, were created in California in the late 1990s. The most widespread styles are rooted in the teachings of three gurus/lineages, each of which have laid claim to being the original and true yoga, even as some of their theories and practices go against the grain of the others:

- Krishnamacharya (think Iyengar, Yoga Therapy, and most forms of “flow” yoga, including Ashtanga Vinyasa);

- Sivananda (from the teaching of Satyananda Saraswati, this approach also influenced the early development of flow styles and more gentle and contemplative styles such as Ananda);

- Gosh (and his leading student, Bikram Choudhury).

Curiously, each of these lineages claim not only to be the “true” yoga but also to most truly root their practices in the ancient Yoga Sutra of Patanjali, which they all say is the fundamental written source on yoga philosophy and practice. Put aside for a moment that the main lineages teach mainly postural yoga, not meditation, while Patanjali wrote only a few words about asana (telling us to be steady, relaxed, and present), yet thousands of words pertaining to the mind and meditation. You may also like to put aside that the Yoga Sutra was never considered an important source of yoga philosophy until 20th century gurus made it so through constant assertion, and perhaps put aside the fact that today’s postural practices simply did not exist when Patanjali lived, despite many of today’s yoga leaders claiming that Chaturanga and 90% of the other postures taught today are ancient.

Indeed, in a guru’s self-elevation and perpetuation we often see incredulous claims. Bikram claims his is the only method rooted in the Yoga Sutra, which he then wrongly dates to 4,000 years ago. In the Krishnamacharya tradition we now have Patanjali being elevated from ancient grammarian and yoga scholar to deity, with serpent-like sculptures of his supposed likeness on a pedestal enshrined at the Himalayan Institute in rural Pennsylvania, which publishes the popular Yoga International magazine and website, this following the example in Pune at the Iyengar Memorial Yoga Institute (shown here).

We also learn from Krishnamacharya’s biographers – most of whom are his relatives and far more hagiographers than biographers – that this truly remarkable early 20th century yoga innovator was not really an innovator, but rather taught what he gained from direct transmission from a 9th century CE sage – Nathamuni – he encountered as a teenager. And we learn from yet another relative that he and his student Pattabhi Jois found the Ashtanga Vinyasa sequence on ancient decrepit manuscripts hidden in a library archive – all of which then decomposed after copying what they could, leaving no record except their own. Bummer for the rest of us who might have wanted to see that source. Oh, and there was Chaturanga!

I’m among those who’ve grown weary of the fanciful stories, exaggerated or outright false claims (Krishnamacharya’s seven years in Tibet studying with [of course] the last remaining true Himalayan yogi, one Rama Mohan Bramachari), and often authoritarian ways (it’s often the guru’s way or the highway, although in some situations the highway can be hard to find).

But my issues in this are rather small in contrast to those of many others, especially women and those not in a privileged situation, whose place in yoga is often seen through the prism of the Bhagavad-Gita’s twin concepts of rta, “right action” based on one’s place (primarily one’s gender and caste), and dharma, one’s “purposeful path,” as in what one should be doing with his or her life, which is determined primarily by rta. One might want to acknowledge that power and influence in yoga – even access to the practice at all in some places and times – has historically been the province of Brahmin caste men, something that has begun changing only in the past two generations and only with the globalization of yoga.

In science (interestingly, a scary notion to a lot of folks in the yoga community, but rarely so to kids who like to discover and learn new things), unlike in religion, we ride the horse of best practices until those practices no longer serve us well in the pursuit of knowing; the anomalies are just too great. So, we dig deeper, or differently, in exploring new concepts that can carry us forward in apparently (or factually) true and meaningful ways. As such emergent insights proliferate, much as we see today in yoga, we come to question the old claims, the received wisdom of the gurus perhaps helpful, and perhaps not.

As with any significant change, these things can be difficult and painful, especially as we may have taken so much for granted, accepted claims at face value, and become altogether clear and comfortable riding that old and not such well-worn horse. As the new and often original explorations continue, new concepts based on stronger sources of truth come to the fore, even if against the often-monumental resistance or opposition of those with a stake in the old paradigm. Eventually, a new paradigm is established, often obscuring what came before, as though the sea has washed away the debris of past errors.

THREE PARADIGM SHIFTS IN YOGA

OLD YOGA PARADIGM

- There’s an original and true yoga that remains unchanged to this very day. There is still only one true yoga.

- Only the original yoga is pure and true. It is the only legitimate yoga.

- Pure and true yoga can only be learned from a guru whose lineage goes back without interruption to the original source.

NEW YOGA PARADIGM

- Yoga arose from multiple source that have cross-fertilized with one another and with other sources to give us the diverse world of yoga we have today.

- Yoga is legitimate when it makes someone’s life better. Its origins are not all that important. New concepts of yoga emerge from practice.

- It’s possible to learn yoga from many different teachers, even those with no guru claims. And the best teacher one will ever have is inside – the inner teacher.

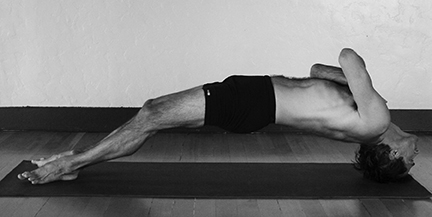

In the new paradigm of yoga, we’re free to explore, practice, and teach without constant review or control by a guru or so-called master. We don’t have to submit to the whims and expectations of our teachers. We are free to accept or not accept the old archaic notions about human anatomy and physiology that are often so misleading or dangerously incorrect. For example, we might reconsider the value of some postures, the very form of which are inherently dangerous, such as Setu Bandhasana (shown here), in which the neck bears significant weight while being forced into extreme cervical hyperextension.

I NO LONGER DO THIS TO MY NECK!

A less extreme example involves the knee joint, which doesn’t twist when fully extended, yet there we are, putting significant twisting force into it when doing Warrior I too soon in a class – specifically, as part of Sun Salutation B. We might also reconsider a few other ancient practices such as bloodletting to cure a headache (a basic Ayurvedic prescription), or snipping the frenulum ligament at the base of the tongue in pursuit of the divine nectar said to be dripping down from the pineal gland.

The new paradigm lets go of hierarchy, authority, and discriminatory practices based on sexist, racist, or xenophobic assumptions. It says it’s okay to question authority, to rethink the concepts, to design more innovative and beneficial practices, and to share them with others in ways we find inspiring and effective.

And yet, we may find it helpful to not simply throw out all use of traditional nomenclature and frameworks in making this transformation, but only so long as when we confront conflicts between traditional approaches to yoga and what we understand about human physiology from modern science, we are not forced to carry on beliefs or practices that make us deny scientific knowledge to our own detriment.

Interested in exploring this further? Stay tuned for more in this little series of posts on yoga as an accessible, sustainable, and thereby more deeply transformational practice.

Namaste.